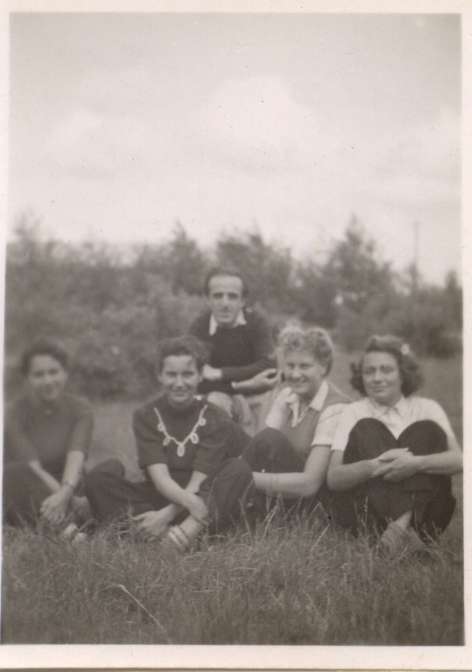

Theodor Pinkowitz (1915) stayed in camp Westerbork for five years, survived and emigrated to the United States. At the end of his life he looked back at his time during the Second World War.

Theodor Pinkowitz

‘I was born into a middle class Jewish family. Strongly religious, my father was a bookseller of Hebraic, Judaïca religious and German literature. He served in World War I in the German army and fought as an officer at the Western front. After the war, he again took up his old occupation, in which he was succesful, but not in the sense of accumulating material wealth. He was actually not a good businessman. He had in his field of endeavour, a very good reputation, and above all possessed an extremely broad knowledge.

I attended a Junior College in Berlin. It was actually much more than a college, as I learned French, English, Latin and Greek. At the very early age of fourteen I became very interested in watching the rise of the Nazi party. Because of my political activities (I had joined an anti-Nazi paramilitary organization) my parents and I decided that, if and when Hitler came to power, I would be in danger, and that I would have to leave Berlin. Consequently, I became one of the first refugees from the Nazis and was certainly one of the youngest. My parents and sister stayed in Berlin. After I was expelled from school because of my anti-Nazi activity, I went to Paris, France, to continue my studies. After two years, when it seemed that the danger was not a threat to my life, at their urging I returned to the home of my parents.

In november 1938 the Germans started a well organized 'action'. They rounded up sixty to seventy percent of all male Jews in Germany, and transported them to the concentration camps. At that time they were not comparable to the extermination camps later in the war. About eighty to ninety percent of the Jewish prisoners survived the first six to eight weeks. They were offered release if they would sign that they would leave Germany within three weeks. Fortunately we were not among these people.

My father and I were at hiding at the so called Kristallnacht on November 10 that year. Through the underground communications we were told that we should try to leave Nazi-Germany and escape to Holland or Belgium. Of course, this could not be done legally, for we did not have passports or visas. My mother and sister insisted that my father should try to get into Holland or Belgium. They would remain in Berlin. We at that time could not anticipate that the Germans would slaughter women, childeren and old people in their infamous concentration camps. After the war ended I found out they had been shipped to a getto in Lodz (Poland) in October 1941. We do not know for certain but we think they were transported to Auschwitz, never to return.

One night my father and I quietly left Berlin by train for Aachen, near the border of Holland. After a few days we got in contact with some Dutch people, who smuggled the refugees into Holland or Belgium by night. We stayed a few days in a hotel in Aachen and, one night at 11.00 pm, the Dutch underground appeared with about six or seven other Jewish men. We joined them and were led through the icy cold night of December 16, 1938. We started out to cross the Holland border having to walk that awful night in knee deep snow, avoiding the German guards, and finally reaching our destination, the city of Heerlen. Arriving in a very deplorable condition, we were welcomed by a Dutch family who fed us and let us rest until the afternoon. We then boarded the train to go to Amsterdam.

This may sound easy, but it was extremely dangerous for us to travel by train in Holland as refugees. Because, Holland had closed her borders with Germany to refugees. If we were caught in any area near the German border they would, without pity, send us back to Germany to be taken care of by the SS. We would then be shipped to the concentration camps inside Germany. My father and I, with a few other people, succeeded in reaching our destination without attracting any attention. We arrived about midnight extremely cold, and were received by some Dutch Jews who met us at the railroad station. They took us home to freshen up before we met our fellow Jews from Germany. On the first night we were brought to a Jewish family, where we stayed until the next morning. Our next move was to report to the Jewish Refugee Committee in Amsterdam. They told us that we had to go to the police and declare our status. We did this, but when we arrived at the large police station a serious difficulty confronted us. We were told to wait a moment – our wait was much more than that, for we were put in cells for four days.

Finally, we were told to take our belongings, which in most cases was not much, not even a suitcase. We had only a briefcase in which we had some underwear, socks and other small items, but not one bit of money, nothing. We were empty handed, in the true sense of the word. With police busses we were taken to a Dutch convent, which was our new home for about six months. Later they brought me to a small camp in Hoek van Holland, near Rotterdam. My father in the meanwhile stayed in the convent in Amsterdam.

Birthday

On July 1, 1942, it was my birthday and my present was to have the feared SS troops take over total control of the camp. The Dutch commander was removed and his position was taken by a high SS offical named Deppner.

In February 1940 I was transferred to camp Westerbork. The camp at that time was built to house about 1.500 people far away from the big cities. Families with children were brought in. Things were pretty good in comparison to Hoek van Holland, and things worked out well in the beginning.

May 10, 1940, the invasion came. We were very tense, not knowing our fate. I went to the barracks, where there was a radio and followed the events of the day. A rabbi came to visit us from a city 100 kms away and arranged for us to leave the camp. A train was at the local station Hooghalen, four kilometres away, that took us to Leeuwarden. There we were received by boy scouts and Christian families, who quickly took us into their homes. A day or two later we were told that the French were coming to fight the Germans and we would soon be free people again. However, I thought that was impossible because France had been invaded the same day, May 10. We ventured out into the streets and found tanks everywhere. The dreaded Swastikas told us they were German Panzer units. We stayed three weeks or so with our kind friends in Leeuwarden. Then we were orderded back to camp Westerbork.

Back in Westerbork life didn’t change a lot for the first two years. Just like before, we had to work. I volunteered to work on the campfarm, just outside camp Westerbork, which pleased me. This was because I could then build up my body strength, and if I was sent to one of the other concentration camps I would possibly survive. I worked on the farm for three years, the soil was very harsh and a lot of the farm was not developed, it was filled with weeds. We started to clear and cultivate these hectares, as every bit had to produce food for the camp and others. I liked the hard work because I was not confined and could see the birds, animals and life going on as usual. Life that was totally unaware of the tragedy happening nearby.

On July 1, 1942, it was my birthday and my present was to have the feared SS troops take over total control of the camp. The Dutch commander was removed and his position was taken by a high SS offical named Deppner. Fifteen days later approximately 2.000 Dutch and German Jews were gathered in Amsterdam and were shipped to Westerbork. We, the older prisoners, were confined to our barracks when this large group of Jews were marched into the camp. Old men and women plus families with childeren made up the group. We sneaked a look from behind our window shades.

The new SS commandant began selecting people, for what purpose we did not know. We were told that the majority of the Jews in Holland would be shipped to work camps in the east side of Germany and Poland. Within hours all the 2.000 people were loaded into cattle cars on the tracks and were gone. We of course began to panic as 200 people from our original group of 1.500 were picked to go to the camps. As I mentioned before, I was a very good worker, and before any more people were sent east, a Dutch farmer who worked in the camp as a supervisor, selected me and two other men from our group to remain in Westerbork. This was in order to maintain the level of production of produce from the farm. So we became teachers and instructed the new people in their work on the farm.

In 1942, a group of old comrades, trusted friends and I made a pact togehter, that we would never leave voluntarily on any of the trains, should we be selected. This group was formed in 1943, and I was placed in another job for this reason. We had a man in the post office, who belonged to our group. He would smuggle letters into and out of the camp for the Dutch resistance organization. This kept us in touch with the illegal underground people and the resistance all over Holland. By this route we were able to get into the camp false documents, verboten (forbidden) other papers and newspapers.

Our man knew that he was on the black list of the German SS, because in the early part of the Nazi regime in Germany, he had operated an illegal printing press printing anti-Nazi posters and newspapers. We were afraid and knew that some day he would be traced by the Nazis.

It was determined that I would replace him. So I stopped working on the farm and started to work at the post office in the camp with political prisoners. I was assinged to work with that man. I spent eight weeks with our comrade who explained everything to me, how we did it and what to avoid. Soon after I had learned to be a forger and printer, he was arrested, taken to the prison in Scheveningen, and shot. I took his position immediately, having first to reorganize the work habits of our group. By bringing false documents into the camp we were able to help approximately 50 people escape from Westerbork. Because of our efforts many prisoners were saved.

The high point of occupancy of the camp was about 18.000 prisoners and there was not sufficient space in the camp, so some had to be kept outside the barracks. Though there were no brutalities such as those that existed in the big camps, there was always great hunger, for not enough food came into the camp. One could still survive if you were fortunate to be left off the list for the next tuesday’s cattle cars to the death camps. Fortunately, these shipments practically ceased in September of 1944.

Through the stupidity of the SS men who were my supervisors in the post office, I overheard the news broadcast of the allied BBC and eventually learned that the war appeared lost for Germany. Our fate was still unknown and we wondered what about future. The events of the war were developing very fast each day. They rapidly progressed after the Allies crossed the Rhine River to the day of our liberation, April 12, 1945. That is the day I shall never forget.

After the war I found out that my father had been sent to the concentration camp at Theresienstadt. Because he had served in the German Army in World War I and had been awarded the Iron Cross he was not slated for extermination. He was liberated by the Russian army and subsequently emigrated to Holland, where he died in 1961.

In 1953 I emigrated to the United States and went into the export/import business. Looking back I can say that I survived terrible ordeal, but the body and mind will not release me from the horrible things that come back to me in the dark of the night. I still feel anguish for my family and friends that I never saw again. My anger at the goverments that drove me as a refugee from my native land, still burns within me. I have remade my live in America, I have married a survivor from another concentration camp. I have a son and he has a family. Life moves on in spite of the sorrow for all the millions that were exterminated.’