After Germany invaded the Netherlands in the 1940s, German racial laws such as the “Nürnberger Rassengesetze” were enforced. “Mixed-marriages” - marriages between Jewish and non-Jewish individuals - were prohibited. In Germany, to avoid public unrest, people in such marriages were often deported later or even completely protected from the transports, especially if they had kids. In the Netherlands, however, those people were worse off than in Germany itself: many were persecuted, sterilized and deported. This policy only changed after direct orders from Berlin itself, stating that matters should not be preempted and the situation should be handled similar to Germany at first. This led to the consequence, that many Jewish persons who were in a ”mixed-marriage” got arrested later than those who were not.

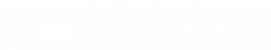

Left: drawing of Westerbork by Leo Kok.

(collection HcKW: https://collecties.kampwesterbork.nl/werk/https%3A%2F%2Fdata.kampwesterbork.nl%2Fwork%2FHCIS.00007821)

Michel van Moppes

- Voornaam

- Michel

- Achternaam

- van Moppes

- Geboortedatum

- 25 december 1901

- Geboorteplaats

- Den Haag

Michel van Moppes was born on December 25th, 1901, in The Hague, South-Holland. His father, Salomon van Moppes, born in Amsterdam in 1858, worked as a salesman and porter. Since 1887, he has been married to his wife Esther Rodrigues, who was also born in Amsterdam in 1864. Michel was the seventh of eight siblings overall.

In contrast to other branches of the van Moppes family, who were big players in the diamond trade, Michel was born into a branch focused on gastronomy, trading and small businesses. In his early adulthood, Michel worked as a window cleaner, a bathroom goods salesman, and a waiter, among other things. He married Anna Erna Helena Meijer, who was born in Regenthin in 1903.

When the Nazis invaded the Netherlands in 1940, the situation got worse and worse for Michel. He then eventually got arrested along with a colleague in July 1944. As a »Mischehefall« (“mixed-marriage case”), he had to spend two days at the police station in Meppel. There, he had to share a cell under inhumane conditions, together with his colleague and another man. They had one cot for all three to sleep on, even though it was designed for one person. After two days on the police station, their further deportation was arranged. They were sent to Assen by train, where an SS-Soldier picked them up at the station. He placed them in a carriage that took them into the Westerbork concentration camp.

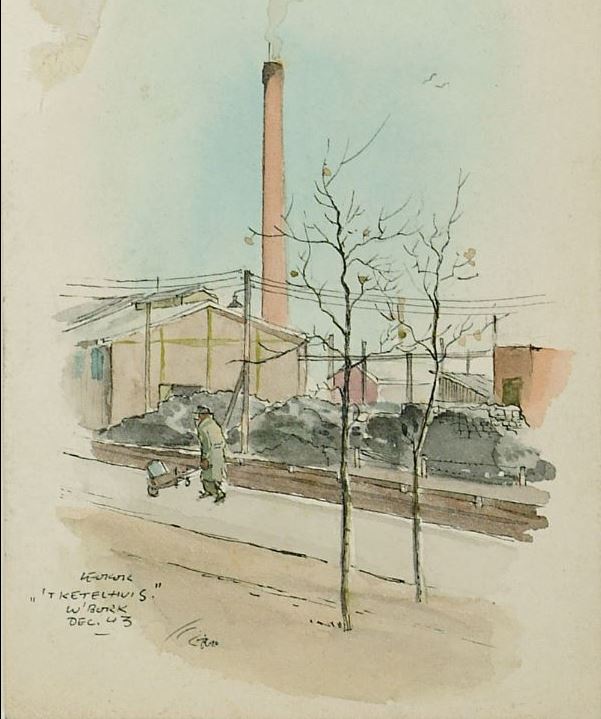

Lagerkarte Michel van Moppes (collection HcKW)

Lagerkarte Michel van Moppes (collection HcKW)

„Eenzaam en verlaten, midden in Drenthe’s heiden, als een graf zoo somber, verheft zich het concentratiekamp Westerbork, omgeven door hoog prikkeldraad, waaromheen op elke zijde drie uitkijktorens, waardoor vluchten is uitgesloten“

(“Lonely and abandoned, in the middle of the Drenther heathland, as grim as a grave, the Westerbork concentration camp stands, surrounded by high barbed wire fencing and with three watchtowers on every side, rendering escape impossible.“)

From: Mijn ervaringen in het Concentratiekamp Westerbork of de toegangspoort tot den dood ~ M. v. Moppes

Like all new arrivals, Michel first had to go through registration. There, his name was recorded in the register and almost all of his valuable belongings were taken from him. He was then sent to barrack 61.

„Denkt U eens in een lange zaal met in het midden een onafzienbare rij bedden, drie hoog en met een tusschenpad aan beide zijden, met bagage aan de hanebalken en de mensen als mieren in het midden der barak“

(“Picture yourself in a very long room, where in the middle are endless rows of triple-stacked bunk beds with narrow aisles on either side. Luggage hanging from the roof beams and people are crowding around like ants.”)

From: Mijn ervaringen in het Concentratiekamp Westerbork of de toegangspoort tot den dood ~ M. v. Moppes

Here, Michel experienced the tough life of a concentration camp prisoner. Everyone needed to get up at 6 o’clock when a strident whistle sounded. First, you showered with all the people from your barrack, in very cramped conditions. After that, you ate breakfast in the crowded barrack. At last everyone needed to come to the parade ground, where they were counted and work was distributed. Michel initially worked in the camp’s cleaning section. He needed to bring trash bins out of the camp on a wheel barrow, where another team was ready to sort it. The first work shift lasted up until 12 AM, and after a short break, the second one began and continued until 6 PM. To leave the camp for work, Michel had a special permission. Furthermore, Michel witnessed the horrible evenings on the day before the transports. On these days, at 9 PM, it was made public that at 3 AM the list of names would be read out. Fear spread throughout the camp and the tension was unbearable. Michel describes the evening of the announcement as following:

„Om negen uur ’s avonds werd dan bekend gemaakt, dat ‘s nachts om circa drie uur een transportlijst zou worden voorgelezen en dat ieder wiens naam daarop voorkwam zich reisvaardig moest maken. Dit gaf dan een geweldige consternatie. Slapen ging zoo’n avond niemand meer en in iedere barak was hoogspanning. […] Een ieder, die maar vermoedde, dat hij op transpoort zou gaan begon in te pakken, wat hij nog bezat. Dan groepte men in clubjes samen en alle gespreken betroffen de vraag: wat zou er met ons gebeuren; waar ging men naar toe? Cellen of Beren Belsen, Theresienstadt, Auswitz of andere kampen? Dan na lange uren van spanning waarin haast niemand sliep kwam om drie uur ’s nachts de barakkenleider. Een doodsche beklemmende stilte trad dan in. Eindelijk begon het voorlezen der namen van hen, die op transport gingen. Werd er iemand afgeropen dan moest hij “ja” roepen en dikwijls gaf dit schokkende taferelen. […] Eindelijk begon dan om zeven uur de droeve optocht naar de wagons, in iederen wagen tachtig menschen (een aanblik om nooit te vergeten).“

(“At 9 o’clock in the evening, it was announced that around 3 AM, the new lists for tomorrows transport would be read out and that everyone whose name was called had to be ready to depart. This always led to widespread panic. No one could sleep on such nights – in every barrack the tension was unbearable. […] Every person with the slightest suspicion to be on the next transport began to pack the rest of their belongings. Every conversation on this evening revolved about the same topic: What will happen to us? Where do we need to go? The cells of Bergen-Belsen? To Theresienstadt? To Auschwitz? Or a completely different camp? Then, after many painful hours of waiting in which nobody slept, the barrack leader entered the building at 3 AM. It became dead silent. Finally the reading of the names began. Every person called needed to answer with “yes” which often led to heartbreaking scenes. […] At last at 7 o’clock in the morning, the sorrowful march to the carriages began. In every carriage were eighty people – a sight burned in your memory forever.”)

From: Mijn ervaringen in het Concentratiekamp Westerbork of de toegangspoort tot den dood ~ M. v. Moppes

´No one could sleep on such nights – in every barrack the tension was unbearable.´

Moreover, Michel needed to spend six weeks in the punishment barrack – a prison inside the prison. He was sent there because he was originally arrested as a »Mischehefall«. On the 1st August 1944, he went into the punishment barrack 67. He had to give up his last remaining belongings, his hair was shaved, and he was issued a prison jumpsuit. The circumstances here were very tough - even tougher than in the rest of the concentration camp. It was cold, no blankets were available, you got up even earlier, and a different work needed to be done.

„Om vijf uur ’s morgens bij den zaalleider op bloote voeten en in je onderbroek, een heel lange rij. […] Om half zes aantreden. […] Voetje voor voetje schuifelen we voort in de grauwe morgenschemering. Het is nog bijna nacht en het motregent. Wij rillen van kou en honger. Dan komen wij aan een lange barak, aan weerszijden door andere barakken geflankeerd. Wij zijn blij, dat we even uit den wind staan.”

(“At 5 AM we needed to line up in front of the hall supervisor. Barefoot and dressed only in underwear. […] At 5:30 AM we had to report for duty. […] Step by step, we shuffled forward through the cold, grey dawn. It was still nearly night and fine drizzle was falling. Shaking from cold and hunger we eventually arrived at a few long barracks, grateful to be out of the wind for a moment.”)

From: Mijn ervaringen in het Concentratiekamp Westerbork of de toegangspoort tot den dood ~ M. v. Moppes

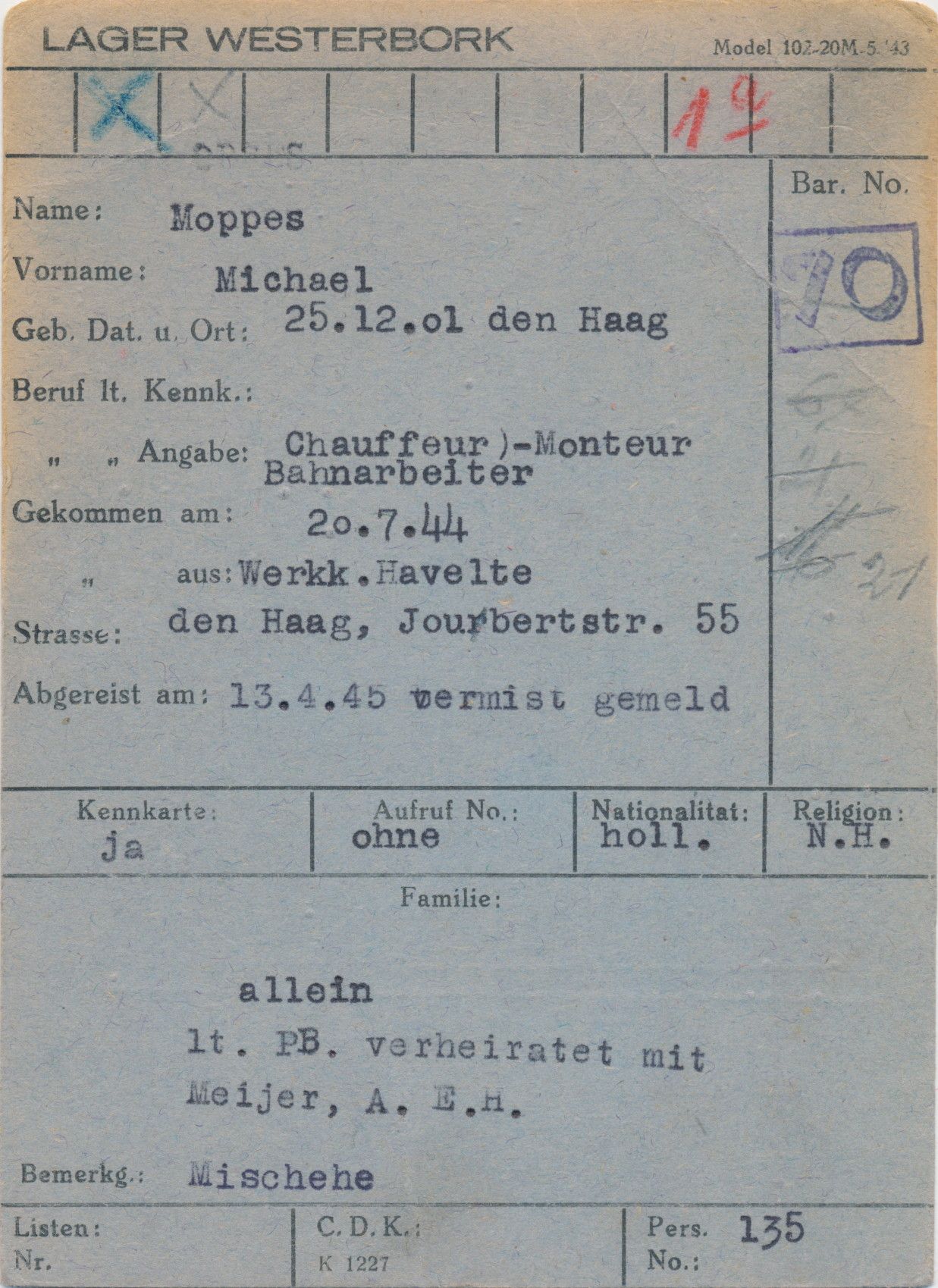

Sonderausweis Michel van Moppes (collection HcKW - https://collecties.kampwesterbork.nl/werk/https%3A%2F%2Fdata.kampwesterbork.nl%2Fwork%2FHCIS.00014567)

Sonderausweis Michel van Moppes (collection HcKW - https://collecties.kampwesterbork.nl/werk/https%3A%2F%2Fdata.kampwesterbork.nl%2Fwork%2FHCIS.00014567)

For work, the prisoners were brought to another barrack. In there, they needed to extract carbon from old batteries in tough, manual labor. To do that, they were given a hammer and chisel to break the batteries open and extract the carbon by hand. At the end of the day, each person should have had 8 kilograms of carbon collected. Moreover, the conditions for work were very unpleasant. Due to the hammering, there was a constant level of loud noise, and carbon dust floated through the air, settling on the tables. Even though the working conditions were that hostile, Michel says that the prisoners from the punishment barrack were unbelievably cohesive and acted almost like a community. Especially two events are stuck in his head:

„Een meisje biedt mij de helft van haar laatste boterham aan, terwijl de honger uit haar oogen staart.“ (“A girl offers me half of her last piece of bread, while one can see the staring hunger in her eyes.”)

„Plotseling groote stilte. Ik sta verbaasd; wat zou dat zijn? Nu klinkt een gezang als een koraal, stijgt een droevig lied omhoog. Ik kan het niet verstaan, maar het is heel mooi. Het ontroert mij; ik ben blij als het is afgelopen, want ik kon mijn tranen maar met moeite weerhouden.“

(“Suddenly, a deep silence falls. I wonder; what is happening? Then a chant rises, a sorrowful song, sung by the prisoners. I cannot understand the words but it is beautiful. It moves me deeply and when it ends I am relieved because I could barely hold back my tears.”)

From: Mijn ervaringen in het Concentratiekamp Westerbork of de toegangspoort tot den dood ~ M. v. Moppes

Prisoners working in the batteryworkshop of Westerbork (collection HcKW - https://collecties.kampwesterbork.nl/werk/https%3A%2F%2Fdata.kampwesterbork.nl%2Fwork%2FHCIS.00021951)

Prisoners working in the batteryworkshop of Westerbork (collection HcKW - https://collecties.kampwesterbork.nl/werk/https%3A%2F%2Fdata.kampwesterbork.nl%2Fwork%2FHCIS.00021951)

Another major event during his time in the punishment barrack occurred on September 13th, 1944, two days before he was scheduled to return to a regular barrack. On this day, a transport departed from the concentration camp - the last one, as it would later turn out. Those days were particularly bad for the prisoners of the punishment barrack, since they had a high risk of being deported via those transports. Michel’s and his colleague’s names were on this transport list as well. That meant that they needed to go on the last transport, two days before their regular time in the punishment barrack would have ended. For that reason, they were both convinced that this must have been a mistake. They talked with a guard, who then talked with his supervisor. It then turned out that it actually was a mistake and they were correct. Shortly before the last transport departed, their names were removed from the list, and they were released from the punishment barrack, which was subsequently disbanded.

„Eindelijk om circa half negen mogen wij de strafbarakken verlaten: wat was dat een spanning geweest; ik kon wel huilen en lachen tegelijk van de zenuwen.“

(“Finally at about 8:30 we were allowed to leave the punishment barracks. A heavy burden lifted as we were allowed to leave, feeling like crying and laughing at the same time.”)

From: Mijn ervaringen in het Concentratiekamp Westerbork of de toegangspoort tot den dood ~ M. v. Moppes

At first, Michel continued to live in barrack 21 and still needed to work hard in all kind of jobs. When the allied troops came closer to the camp, the Nazis began to abandon it. The prisoners had to help them pack their suitcases and packages onto trains, using the opportunity to plunder and steal. In the meantime, they also prepared to take over the camp, as soon as the Nazis would have left. At some point, a gathering is set after the Nazis disappeared, but during the gathering, news spread that allied tanks are rolling towards the camp. In the upcoming chaos, Michel took his shot and escaped through a torn fence near the hospital. A farmer couple nearby gave him a bed for the night before he eventually joined the Canadian troops. He fought alongside them at the front, where he faced several dangerous situations. In the end, he survived until the war ended, then left the Canadian forces in Utrecht and visited his wife in The Hague, reuniting with her for the first time again.

He stays married to her up until 1950. Around 1958, he married again. Leopoldine Burian became his new wife, who was formerly married to Michels brother, who died in the war. Many of his siblings fled Europe; three were killed under the national-socialist reign of terror. Joseph was murdered in Auschwitz on May 3rd, 1944. Herman was arrested on April 7th, 1942, went to the prison in Scheveningen, then to Kamp Amersfoort, and eventually was deported to the concentration camp Mauthausen, where he died around March 31st, 1942. Jacob was arrested on August 2nd, 1942. He initially managed to hide in Scheveningen, but was betrayed and arrested again. He was first sent to Westerbork, where he stayed for a week before being deported to Auschwitz, where he dies in March 1944 near the camp.

102.000 stones at the site of camp Westerbork for all victims (collection HcKW)

This portrait was written by Johannes Brandt, who works as a volunteer for ASF at Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork.